The Year of the Miracle Along the River Vistula

At the end of World War I, on 11 November 1911, an independent and sovereign Polish state was created again, for the first time in 123 years. Thus, in the interwar period and after the systemic change of 1989, the most import- ant national holiday in Poland was 11 November. The other national holiday of similar importance falls on 15 August. The latter day has multiple meanings: on the one hand, Roman Catholics celebrate the day as the Assumption of Mary, thus it was generally considered as anti-regime manifestation. On these days, tens of thousands of people gathered at the square in front of the monastery of the Order of Saint Paul at Częstochowa or at the Benedictine Monastery of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska near Krakow. After the systemic change, 15 August became an official holiday to celebrate. Since 1992 this has also been the day of the Polish Army since the Polish army defeated the Red Army near Warsaw this day in 1920. Considering the circumstances of the battle, no surprise that the religious event and the battle of historic importance have been intertwined. The stake at the battle of Warsaw was no less than the survival of the hardly two-year-old state and the Red Army outnumbered the Poles, thus victory was a miracle. In Polish memory politics the battle appears as the “Miracle at the Vistula” that saved Poland and Europe from the Bolshevik army. This is the event that Poland commemorated on 15 August 2020.

The Polish nation celebrated the end of World War I as a victory. Thus, preserving the status quo was a top priority for the political elite. Moreover, after having defeated and pushed back the Bolsheviks as well as acquiring territories in the West (Greater Poland) and in the South (Silesia [in Polish: Śląsk] and the Zips [in Polish: Spisz]), this elite had regional ambitions. During 1920, Marshall Józef Piłsudski the “father of independence” defined his policy to preserve the sovereignty, as well as independence and integrity. The central element was the way to ensure that the two neighbouring powers, Germany and Russia, would never be able to divide Poland among themselves. Piłsudski’s response was a plan for a Central European federation that, in his concept, would be the cooperation of nations that had lived in the former territory of the Jagellonian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Republic against Bolshevik Russia.

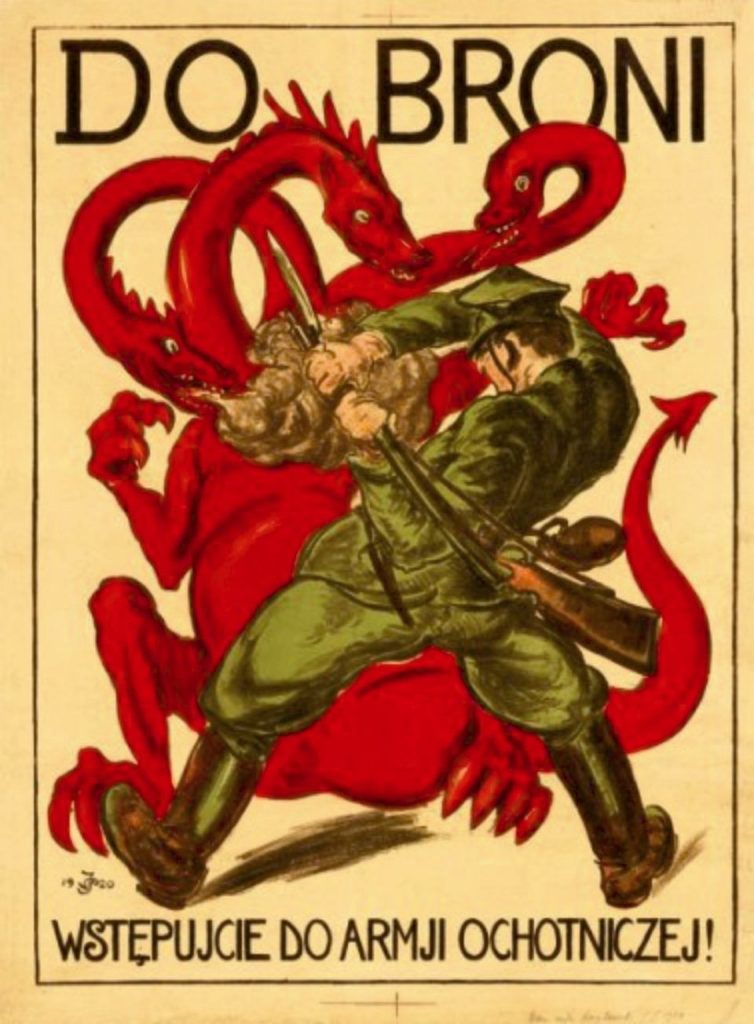

Propaganda poster from the period of the Polish-Bolshevik War of 1920

The Polish statesman believed that the interests of Poles, Ukrainians, Belarussians and Lithuanians were common. The federative structure that they imagined would have included Poles, Lithuanians and Belarussians (i.e. the former Lithuanian Grand Duchy) in the same state and a federation with an independent Ukraine, which was in the making. According to Piłsudski, this could have been realized exactly in the year 1920. However ambitious his plans were, he missed taking the Lithuanian national awakening and its anti-Polish content into consideration, and he also disregarded the fragility of the Ukrainian national consciousness as well as that Ukrainians did not perceive the Bolshevik threat as a fatal danger. At the same time, we shall recognize that if Piłsudski’s plan had been realized, there would have been a buffer zone set between Poland and the Soviet Union which came into existence soon thereafter. Eventually, the Peace Treaty signed in Riga on 18 March 1921 created another framework. The buffer zone was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union and the Lithuanians, Belarussians and Ukrainians who landed on the Polish side, thus failed to receive autonomy. Therefore, when Piłsudski apologized for the Treaty to the Ukrainian units that fought along with him, it was not a gesture out of proportions.

Yet, Piłsudski’s concept remained the baseline of the Polish foreign policy after 1989. The goal was to create or maintain a clear division between Russia and the nations mentioned above in political, economic and cultural terms. The Russian annexation of Crimea increased the level of Polish anxiety to a level not seen in the last 100 years. Thus, in the course of the centenary celebrations of 2020, memory politics focused on the Polish-Ukrainian alliance and the anti-Russian elements of their common history.

The way the Hungarians’ role came to the foreground was an interesting sidestory of the memory politics of this alliance. It was for Pál Teleki’s first government that provided munitions’ supply to the Polish army, which proved decisive during the battle of Warsaw. In the past decades, a number of Polish settlements have inaugurated memorials to recall this support. Among these, one stands in front of the railway station of Skierniewice, where the cargo of arms reached. The plaquettes in the city of Warsaw and in Ossów commemorate the event, too. In 2020, new monuments were erected. First, the statue of Pál Teleki was unveiled in Krakow, then a new plaquette was presented in the small town of Brok, finally, a group of statues, that of Charles de Gaulle, Pál Teleki, Simon Petljura and Józef Piłsudski were erected in Skierniewice. The statues reprensent the group of politicians who provided real aid to Poland in the fight against the Bolsheviks. This was quite a unique contextualization of the post-Trianon Hungarian politics – this is a novelty in terms of the international context and not only if we juxtapose it with how Hungarians tend to perceive this history.

The events of 1918 and 1920 are the foundations of the current Polish memory politics. They are the symbols of realizing and securing independence. Most importantly, those events are not only commemorated and celebrated, but also they serve the essence of their content resurface in the current domestic and foreign policy.