Is Europe really Christian?

It’s undeniable that European (Western) civilization was born of Western Christianity. At least, that’s what many famous thinkers have said.

- Christopher Dawson (1889–1970), a great British historian of religion and culture, said: “Religion is one of the great motors of history and a crucial factor in the rise and fall of civilizations.” [i]

- For Max Weber (1864–1920), German economist and sociologist, four of the five “world’s religions” – Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Confucianism – are associated with major civilizations.

- Samuel P. Huntington, in his bestseller The Clash of Civilizations (1996) wrote: “Europe ends where Western Christianity ends and Islam and Orthodoxy begin” [ii]. And also: “the term ‘the West’ is now universally used to refer to what used to be called Western Christendom.” [iii]

The term Europe was first used, since the advent of Christianity, by the Irish monk Columban (543–615) in two letters to the Pope, in which he used the word ‘Europe’ to designate the part of the world subject to the Pope’s spiritual authority.

If one’s look at a map of Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries in medieval times, he will realize that it’s an almost perfect outline of the European territory.

Europe is also the part of the former Roman Empire that was able to resist the relentless Islamic assaults:

- The Arabs’ advance was halted in 732 at Poitiers by Charles Martel.

- Two centuries later, resistance to repeated Saracen assaults from their base in the Maures massif (southern France), from which they were finally driven out in 990.

- Regular assaults were also carried out from the Iberian Peninsula, which had been under Muslim occupation since the 8th century and was not completely liberated until seven centuries later, at the end of the 15th century.

- But as they were driven out of the south-western part of Europe, they returned via the south-east from the Balkans. After the fall of Constantinople (1453), Ottoman troops led repeated assaults on Europe, finally triumphing in 1526 at Mohács in Hungary, the beginning of a hundred and sixty-year occupation of Eastern Europe, which ended with the failure of the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683. For these one hundred and sixty years, Hungary was, at its own expense, the bulwark of Christian Europe.

Why and how Europe de-Christianized?

Christianity invented secularism: “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s” – “My kingdom is not of this world”. The distinction between the temporal and the sacred is specific to Western Christianity. This is not the case with Orthodoxy (submission of the church to temporal power) or Islam (submission of temporal power to religious power).

The disjunction of the sacred and the profane has had one advantage for man: he is both a citizen and a religious being. He is not 100% dependent on any institution, and this duality has created a space between State and Church that is conducive to the emergence of freedom.

It follows that Christianity is the religion of the personhood. Christianity declares that the human person has an inalienable dignity, because man was “created in the image of God”, and because God himself became man in Christ. A consequence of Human dignity is, in particular, freedom of conscience.

Another major contribution of the Church in favor of the individual: the Church has greatly promoted the freedom of the individual in relation to his family by promoting marriage by choice, freely consented to by each spouse. The Church also favored “neolocal residence”, meaning that newlyweds found their home independently of their respective families.

This fundamental freedom conferred on man by Christianity is what led to the emancipation in the Age of Enlightenment, to religious freedom, to progressive secularization, the culmination of which is today’s rejection of religion.

This movement of ‘sortie de la religion’ ‘away from the religion” (an expression of by Marcel Gauchet, a contemporary French historian and sociologist) – is, paradoxically, a consequence of Christianity, which has promoted human emancipation.

Why is de-Christianization a danger for Europe?

There are at least three types of danger.

First danger

Contemporary secularism is no longer a distinction between powers, each with its own power, but a strict separation that has led to the elimination of religion from society.

There is no longer any counterweight to temporal power. The temporal power has absorbed the moral sphere, and today human institutions dictate moral values (‘values of the Republic’, ‘values of Europe’). These values, detached from transcendence, have progressively distanced themselves from Christian principles to the point of opposing them.

Contemporary secularism thus leads to the following paradox: the separation of Church and State leads to the disappearance of the separation of the two powers, as the distinct spiritual power no longer exists, the moral sphere having been absorbed by the temporal power. The problem is that if temporal power is left on its own with no counterweight, this leads inexorably to a totalitarian state. This is what is happening in France and in several other European countries. This is the first danger of de-Christianization.

Second danger

The world increasingly hates the West: as Huntington said in 1996: “the revival of non-Western religions is the most powerful manifestation of anti-Westernism in non-Western societies. That revival is not a rejection of modernity; it is a rejection of the West and of the secular, relativistic, degenerate culture associated with the West.” [iv]. The phenomenon has since gained momentum.

Third danger

If you chase religion out of the public sphere, it will come running back! (Because nature abhors vacuum) – It will come back in other forms:

- Islam, which is taking advantage of Europe’s spiritual apathy to increase its footprint;

- “Secular religions”, like woke “cancel culture” ideology.

If Europe continues to reject its Christian roots, it is doomed to disappear, because another religion and another culture will settle there, and the consequence will be a loss of freedom and dignity for the human person. Geographically speaking, it will be Europe, but it will no longer be European civilization.

Can Christianity save Europe?

I propose to approach this question first by asking the opposite question: “Can Europe save itself from Christianity?”

Europe, particularly France with its radical concept of secularism, ‘laïcité’, is doing everything it can to get rid of Christianity. A few examples: we no longer speak of Christmas, but of end-of-year celebrations. Catholic schools are increasingly restricted and controlled. Religious statues are being removed. So-called “common values” and “societal” laws are increasingly at odds with evangelical principles and the so called ‘non-negotiable principles’ laid down by the Catholic Church [v].

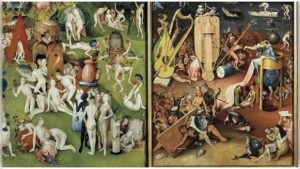

Radical secularism wants to eradicate all religious manifestations from the public arena. But it’s as if someone wanted to rip off his own skin, or tear his heart from his chest, because European civilization is deeply impregnated with Christianity: art (music, painting), cultural heritage (cathedrals), even secularism is a Christian principle!

When Notre Dame de Paris burned down, it has aroused deep emotion in all French people, whatever their religious beliefs. And the secular French state will rebuild the cathedral in 5 years!

So, perhaps in the future, there will be dramatic situations that will give rise to virtuous acts and provoke an awakening, because it’s when an asset is in danger that we realize its value the most.

Can Christianity save Europe?

Two quotes to shed some light on this question:

Christopher Dawson wrote over 70 years ago: “It was the age of Tiberius and Nero that saw the coming of Christianity, and the breakdown of the giant fabric of the world state in the third century was followed by the rise of the new Christian culture. The present crisis or our civilization can only be solved by a similar process of radical conversion and spiritual transformation […]. Civilization can only be creative and life-giving in the proportion that it is spiritualized. Otherwise the increase of power inevitably increases its power for evil and its destructiveness.” [vi]

Mgr. Ketteler (1811–1877), bishop of Mainz in the 19th century: “Founded, at its origin, without the support of physical force, by the sole power of the word and of grace, by the virtues of Christians and the blood of martyrs, it is by the same means that the unity of faith must be re-established and that it will certainly be.” [vii]

The real question is: will it happen in Europe or elsewhere? It’s up to us!

This article is based on Pellet’s essay Geopolitics and Religion – The role of Christianity in Europe’s hegemony and decline published by the Szent István Institute in 3 languages (Hungarian, English and French).

[i] Christopher Dawson, Dynamics of World History, p. 128, LaSalle, IL: Sherwood Sugden Co., 1978

[ii] Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, p. 158., Simon & Schuster, 1996

[iii] Huntington, p 46

[iv] Huntington, p. 101

[v] In particular, in Pope Benedict XVI’s post-synodal apostolic exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis, §83

[vi] Christopher Dawson, Understanding Europe, p. 204, The Catholic University of American Press, Washington D.C., 2008

[vii] Quote from Comte de Montalembert’s Malines speech L’Église libre dans l’État libre, p. 99, in Journal de Bruxelles, August 25–26, 1863

Photo: alamy