Americans prepare for their most popular and most original holiday, the Thanksgiving holiday, on the fourth Thursday of November each year. Not surprisingly, being aware of the extremely divided social, cultural, religious and political climate in America, the highly controversial issue of renaming or even abolishing Thanksgiving (Thanksgiving) came to the forefront again.

With the current upsurge of society-transforming New Left experimental movements, the idea of introducing aFriendsgiving holiday (a merry get-together of friends?) instead of a prayerful Thanksgiving, which generated quite a fierce social debate and outrage in the United States, has been back on the public agenda since it emerged a few years ago.

On the one hand, due to the initiative’s completely secular and contrived message and its content (a celebration of eating and drinking together), which is typical of a consumer society, it also provoked strong opposition from many, and, on the other hand, the initiative’s overtly de-religious objective, devoid of any theological message or content, provoked even greater opposition from more conservative, religious Americans (nearly half of American society). Of course, this is not a completely new phenomenon either, since similar and even more scandalous objections were already raised at the end of the 19th century, mainly by the then already well-known British-born radical utopian socialist thinkers. A similar figure was, for example, C. B. Reynolds, the famous anti-religious secularist politician who was even sued by Protestant denominations in New Jersey for his scandalous statements in 1887 for blasphemy. Not surprisingly, in 1891, Reynolds’ scandalous opinion that neither the great Presidents John Adams, Abraham Lincoln, nor the equally deeply religious contemporary President Grover Cleveland “should have made so much mention of Almighty God at the Thanksgiving table, for it is only a family dinner and should not be spiced with theology over pumpkin pie (…)” He even added mockingly that “if ministers want a religious festival, let them have it in their churches, not in the homes of Americans!” The same argument is raised again more than a hundred years later in American far-left and anarcho-secular libertarian circles, now not only because of the Thanksgiving holiday, but because of the “Christian Christmas” and its unilaterally religious origins, in fact its exclusionary message, which they believe only makes many feel bad and causes resistance. Here we are not able to analyse the anti-religious and anti-clerical ideology and content of these assumptions in depth, but behind this line of thought the underlying denial and rejection of the puritan Protestant morality, faith-based and essentially Christian civilisational heritage that has defined American society and state structure is rather evident, as was demonstrated and analysed by many in the last century, from Reinhold Niebuhr, Russell Kirk, and Samuel P. Huntington to Gertrude Himmelfarb.

Just as conservative religious Americans and opinion leaders in the 19th century tended to blame these initiatives on profane, overly secular and anti-clerical forces and “foreign” anti-Americanism, so in the 21st century the primary sources of the celebration-destroying social experiment and debate are primarily the anti-clerical, anti-religious progressive, postmodern, neo-Marxist, deconstructionist academic intellectuals and the increasingly politically and socially influential militant self-styled social justice warriors and their supporters.

The very popular Thanksgiving holiday, with its controversial origins and perception, is obviously not just about some 40 million turkeys consumed each year, but also about the history and heritage of Europeans in the Americas in the 17th century, with its sparkling and dark sides. In fact, Americans are celebrating the American emergence and adventurous providential survival of the Puritan Calvinist church (the communion of living saints), expelled and driven out of England. Under the leadership of the young William Bradford (English trainee carpenter and self-taught Puritan preacher), the first exemplary democratically elected settler governor, the first English settlers (religious refugees) appeared on board the famous Mayflower , off the coast of Massachusetts, in New Plymouth Bay. Only about half of the tiny group of 105 English pilgrims managed to survive the first very harsh New England winter, not least with the help of 90 members of the friendly local indigenous Wampanoag Indian tribe and their chief, Tissquanto, who introduced the European newcomers to exciting and tasty new foods such as corn, pumpkins, squash and a delicious large wild bird, the indigenous American turkey. According to semi-authentic tradition, these were the ingredients of the first Thanksgiving feast (no reference to eating turkey, by the way), which they ate in peace with the natives in the autumn of 1621, after the first American harvest, of course in eager thanksgiving to the Almighty for their new life and work in the New World. In fact, according to many, it was only John Winthrop, the legendary preacher and governor of Massachusetts, arriving with the second great wave of Puritan pilgrims in 1630, who proclaimed the first Thanksgiving feast in 1637, for different reasons but in a similar religious spirit.

While the celebration of the 400th anniversary of this historic American event was virtually overthrown last year by the restrictions imposed by the Coronavirus pandemic, it is no exaggeration to say, in agreement with conservative realist American historians, that today’s United States could not really exist without the morality, spiritual heritage and, especially, without the precedent-setting model of the famous 11 November of 1620Mayflower Compact model of the Puritan Pilgrim Fathers of Massachusetts of 1620 and 1630. This latter document was shown to have provided a strong intellectual and legal basis for the constitutions of many New England colonial states, as well as for the spirit and wording of the American Constitution of 1787.

In addition to the above-mentioned historical deconstructivist extreme leftist anti-Americanism and anti-religious nationalism, recent decades have also seen the emergence of historical critiques and society forming efforts by indigenous American Indian tribes, which, while to a significant degree well-founded and legitimate, are exaggerated and antagonistic. According to the understandably enervated but obviously ahistorical, retrospectively racial grievance-based (non-White victimology) remarks of indigenous Americans, Thanksgiving is a popular American tradition, a family holiday, based, nevertheless, on half-truths and mostly lies by European settlers. In their view, the Puritan European newcomers in the 17th century did not regard the American Indian tribes who initially helped them as civilised human beings, but rather as savages, simply because they (the natives) were not Christian in the accepted concept of the era. The above mentioned Wampanoag chieftain Squanto, known as a positive hero, and some of his companions were either kidnapped by the settlers in 1622 or taken to England, partly of their own free will, and presented as “noble savages” even to the royal court. This moment also counts as a negative historical aspect in the memory of indigenous Americans.

However, for the sake of historical accuracy, it is important to note that it was not the deeply religious Puritans of the New England colonies who were responsible for the extermination of the native Indian tribes in the second half of the 17th century, but rather the later arrivals of so-called English adventurers and the French colonists in Canada, who did not really follow the teachings of Christ when dividing the New World. Indigenous leaders, and especially liberal decolonialist historians, believe that Thanksgiving should be freed from the burden of false sense of history and tradition. It should instead be renamed Indigenous Remembrance/Food Festival Day, as an indigenous American national day of remembrance and mourning, to retain its popular family-style gastronomic character, or an alternative indigenous American holiday in America, along the lines of Columbus Day on October 12, another historical holiday of controversial significance. In contrast, it is more than indicative that only a few thousand of the nearly 5 million Americans of indigenous descent or identity have signed the petition for a renaming initiative .

All of this makes American Thanksgiving perhaps the most historically inspired family and religious celebration in American society since its official declaration as a federal national holiday in 1863, amidst political, racial and ideological debates. However, in addition to the ideological, cultural and controversies that preoccupy the more educated, historically authentic American social strata, one can say that another significant (perhaps larger) section of American society will only be paying attention to the quality of the hearty turkey dinner and the outcome of the post-Thanksgiving American football game and the fake promotions of the subsequent Black Friday consumer holiday.

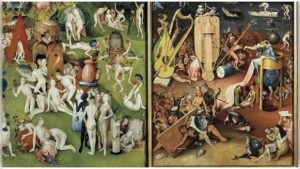

Opening image: A popular depiction of the first Thanksgiving. Source: Britannica