“Czechoslovakians” and the Memory of “Year 0”

28 October, the day of the declaration of the Czechoslovak Republic in Prague was a national holiday of Slovaks during the interwar period. Fol- lowing the fall of state socialism and the disintegration of Czechoslovakia in 1993, for nearly three decades, it was only the Czechs who officially cele- brated it. We shall mention that, starting from the 1990s, there were members of the Slovakian political elite who kept proposing that it should also be- come a national holiday in Slovakia. Although the place of Slovakia within Czechoslovakia is often the matter of debate, the most relevant arguments for seeing 28 October as a turning point in Slovak national history are the following: Slovaks became a constitutive nation of a state in October 1918. This was the first time that its boundaries had been marked. Moreover, the Czechoslovak state was the one that made it possible to lay the foundations of the economic, social and cultural modernity of today’s Slovakia. November 2020 brought about a major change in this debate: the Slovak Parliament voted in favour of adding 28 October to the list of national days even though it did not become a holiday.

It is widely known that 1918 was a turning point in the history of the Czech nation as it was no less than the renewal of Czech statehood. Czechoslovakia was one of the most democratic political systems of the Central European region at the time. This also means that for the Czech society and political elite the jubilee in 2018 had major importance, while the 100th anniversary of the Trianon Treaty caused less excitement among academics and in public life. In Slovakia, the situation was quite different.

There, the frame within which Slovaks interpreted the Trianon question shifted as a result of a large event on 2 June 2020 when Prime Minister Igor Matovič received a hundred ethnically Hungarian public figures of Slovakia at the castle of Bratislava. It was for the first time that a Prime Minister of Slovakia declared that historic Hungary was part of the common past and that he understood why Trianon hurt Hungarians. This indicated that Slovak politicians were willing to make the link between Trianon and the long-term survival of the Hungarian minority. It had not been the case earlier. If the question occurred in public politics at all, Trianon meant the departure of Slovaks from Hungary, thus it was framed as a success story, just the oppo- site of the trauma that Hungarians associated with it.

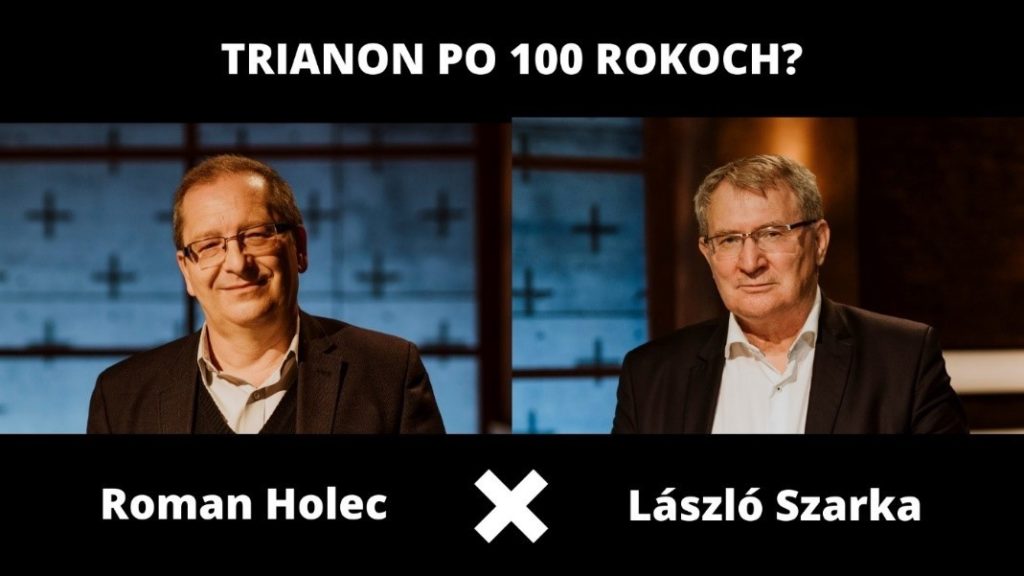

Various Slovak media channels asked several intellectuals and public figures about the topic. TV channels broadcasted interviews and talks on Trianon and about the Hungarian minority in Slovakia. Slovak authors published new books among which we shall primarily mention Roman Holec’s book Trianon, diadal és katasztrófa [Trianon, victory and catastrophy] written in a reader friendly style and Ondrej Ficeri’s A Trianon utáni Kassa [Kosice after Trianon]. This interest reached so far that an academic research group started working on the Trianon Treaty under the leadership of a professor of legal history Erik Štenpien at the Department of Law of the Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice.

ramme called Do kríža. Source: facebook.com/dokriza

Outstanding experts, such as László Szarka, László Vörös and Štefan Šutaj, whose work cannot be labelled ethno-centric or nationalist, had the oppor- tunity to talk of Trianon in prime time on television. On 3 June, the Slovak state television broadcast the discussion programme called Do križa, then hosted by Štefan Chrappa and Jaroslav Daniška, in which László Szarka and Roman Holec debated about currently relevant aspects of the Trianon phenomenon. Importantly, Roman Holec mentioned that he believed the Trianon treaty was unjust.

Of course, in 2020 there were also some who remembered Trianon as a positive thing for Slovaks. For example, despite the erstwhile cultural associa- tion, Matica Slovenská announced that the anniversary could be an occasion for learning about each other, several of their local branches organized fes- tive events on 4 June. Moreover, one could also encounter explicitly anti-Hungarian interpretations and publications, such as Edita Tarabčáková’s work bearing the curious title Sérelem érte a magyarokat? A valódi igazság Trianonról [Were there real injustice against Hungarians? The truth about Trianon], for example. Overall, the events reflected that Trianon has not become an issue of primary importance for the majority society of Slovakia, yet it is also clear that there is a growing number of Slovaks who understand the sensitivity of Hungarians (both of those who live in Slovakia and of Hungarians in Hungary).