Over the summer, the Moldovan leadership and the leadership of the Moldovan breakaway region of Transnistria, which borders Ukraine but does not receive international recognition but enjoys Russian military, political and economic support, kept sending each other increasingly fierce messages. The Russian Foreign Minister has now also joined the messaging, “reminding” the Moldovan leadership that Russia will defend the interests of Russian speakers by all means.

The attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022 changed the essential geopolitical situation in Eastern Europe, despite the fact that, contrary to initial expectations, the Russian army failed to capture the south-western part of Ukraine bordering the Black Sea, and the Republic of Moldova. In 2014, there were heavy confrontations in Odessa, which is in the centre of the region, but this year’s military action did not involve a Russian ground offensive. This is somewhat reassuring for Moldova, as the easternmost strip of territory recognised by the international community is not under the control of the Chişinău government. This area, called Transnistria, in its own terminology the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), was taken under control in 1990 by the 14th Soviet (now Russian) Army, whose leaders and soldiers, mostly Slavic-speaking, originating in the region, feared that, after the expected break-up of the Soviet Union, Moldova would be incorporated into Romania, along with the Slavic-majority region. Moldova eventually retained its independence, declared in 1991, but the Transnistrian region was not under the control of the Moldovan government. This territory was first named occupied by Russia by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe on 15 March 2022, in the context of Russia’s withdrawal from the CoE.

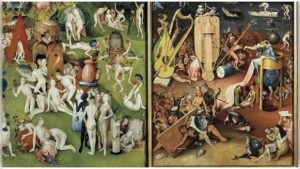

From a security point of view, Transnistria creates a sensitive situation: its defensibility is questionable but, with Russian forces stationed there, any military action would effectively mean a war against Russia. Transnistria is considered as a major arms depot: some of the Soviet weaponry withdrawn from Hungary is stored in Bender Castle, the same castle as where Baron Munchausen served in the Russian mercenary service during the Russo-Turkish war of 1735-39, and where legend has it that he flew across the Dniester River while sitting on a cannonball. On the other hand, the territory functions as a military outpost: the strategic objective of the Russian offensive in southern Ukraine was to secure Transnistria’s physical connection with Crimea and thus eliminate its enclave status, which did not happen due to the stalling of the Russian military offensive. Nevertheless, the region poses a security risk for Ukraine and Moldova, and it is no coincidence, for example, that, on 26 April 2022, unknown persons blew up two of the most powerful telecommunications antennas for the transmission of Russian radio broadcasts in the Transnistrian town of Maiac.

The situation in Transnistria escalated recently, after Transnistria’s “foreign secretary” Vitaly Ignatyev spoke in Moscow on 22 July, on the sidelines of a conference marking the 30th anniversary of the Russian military coup in Transnistria, stating that Transnistria wanted to become part of Russia, in line with the outcome of the 2006 referendum. On 15 August, the Moldovan Deputy Prime Minister Oleg Serebrian, in charge of reunification, publicly stated that, given the efforts of certain forces to destabilise Moldova, the Chişinău government must be prepared for all eventualities, but its priority is to maintain dialogue and the status quo for the time being. In response, Transnistrian “head of state” Vadim Krasnozelsky called on Moldovan President Maia Sandu for peaceful dialogue, and Transnistrian chief negotiator Vitaly Ignatiev said that they had received no response to their offer of talks with the Moldovan authorities, neither in February nor in August, while Sandu’s policy takes Moldova further away from neutrality towards Ukraine, and that “what is happening in Ukraine today is a direct consequence of the failure to reach an agreement at the negotiating table”.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov joined this series of events on 31 August, when he reminded Chişinău that Russia is doing everything possible to protect the interests of Russian-speakers in Moldova. This should be seen in the light of Russia’s frequent actions against certain former Soviet states in the post-Soviet region, mostly on the grounds of protecting Russian speakers living in the so-called frozen conflicts of the early 1990s, which it used partly as a justification for the 2008 Georgian-Russian war. The 2014 action against Ukraine created new frozen conflicts, and one of the pretexts for the 2022 attack was to protect the Russian-speaking population of the breakaway regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

On 31 August, Lavrov called on Moldova, “which is not willing to do so under pressure from the US and the EU”, to engage in dialogue to guarantee regional security, to which “Moscow and the Transnistrian authorities would always be open”. He added, as a hardly hidden threat, that it would be fortunate if the Chişinău government would stop “the geopolitical games imposed by the West and concentrate on the interests of the people living in the country”, as there is also a region in Moldova called Gagauzia, which also seeks a special status, only some elements of which it holds today. (Gagauzia is a region of Moldova, whose Orthodox population, speaking the Gagauz language (which is close to Turkish), tried to rely on Moscow in the early 1990s, also because of Romanian territorial aspirations, but which was eventually granted territorial autonomy in 1994 in the country, and which today is subject to significant influence from Turkey, alongside Russia.) Russia is thus deliberately exploiting ethnic tensions to achieve its own goals and undermine stability in the Eastern European region, while there is no real intention on the part of the states concerned or international organisations to actually resolve minority issues beyond words.

(The cover picture is of Bender Castle in the distance, and the intertextual picture is of Baron Münchausen’s bust and cannonball in the castle. The pictures were taken by Gergely Prőhle, Director of the NKE STI in 2018.)