Sacred sites in the shadow of war

This November marks the 50th anniversary of the signing of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, which is intended to promote the conservation of cultural and natural properties of outstanding value to humanity and to protect them from various challenges, including security. However, in the light of the experience of the last half century, how successful has it been in protecting our built heritage, caught in the crossfire of armed conflicts, often triggered by religious or ethnic tensions? Without aiming to give an exhaustive list, this short overview aims to highlight the opportunities and shortcomings of international protection in connection with a few religiously important sites under World Heritage protection.

Today, the World Heritage Convention, adopted in 1972 under the auspices of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), has become the most widely ratified international convention. Perhaps the best known of these is the World Heritage List, which now includes 1154 sites in 167 countries around the world[i]. Around 20 percent of this extensive list are holy sites, places with a religious or spiritual context,[ii] protecting the world’s religious heritage is a key focus of the organisation’s activities.

UNESCO itself was created by nations learning from the devastation of the world wars, so it plays an important role in maintaining and restoring peace in the ‘soft’ areas it represents (education, science and culture). In the field of cultural heritage, the primary international legal instrument for ensuring wartime protection is the 1954 Hague Convention and its Additional Protocols but, in order to protect World Heritage properties of outstanding value, the States Parties to the World Heritage Convention decided, already during the drafting of the Convention, to establish a special mechanism, namely the List of World Heritage in Danger. The World Heritage sites that are added to this list each year are those that, according to the organisation, require special attention and more effective international action to guarantee their protection. Listing can be justified either by challenges in peacetime (e.g. climate change, natural disasters, tourism development, adverse impacts of urbanisation) or in times of armed conflict (collateral damage or targeted attacks). However, the dominance of the latter is illustrated by the fact that 22 of the 36 cultural sites currently on the World Heritage “Red List” were enlisted in a war context in six countries (Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Mali and Libya).[iii]

This figure, and the examples that will briefly be presented below, also reflect the fact that social tensions along religious or ethnic fault-lines, potentially leading to violence, political instability and the activity of terrorist organisations constitute a particular threat to the built heritage of the social groups affected by these challenges. The reason for this is the symbolic character of these sites, embodying community identity: a monument, a mosque or a church can easily have parallels with the national, ethnic or religious group that is organised around it. Consequently, the attacks against them can be interpreted as a kind of symbolic attempt to occupy spaces of the opposing side, as a modern form of iconoclasm.

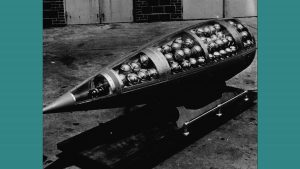

The toppling of the Buddha statues in Bamiyan

The two monumental 6th-century stone Buddha statues that dominate the skyline of the Bamiyan Valley in central Afghanistan are a historical trace of the Buddhist communities that settled along the Silk Road, crossing the valley. And although by the 10th century the region had been Islamised by the Muslim conquest, the statues remained intact[iv]and have become a symbol of the Shiite Hazara people living in that region. The blowing up of the statues, considered idols by Salafi ideology, was ordered by Mohammed Omar, the founder of the Taliban, on 26 February 2001, and became an element of the Taliban’s conquest and of its policy against the Hazara minority, representing around 10 per cent of the country’s population. UNESCO had already drawn attention to the threat to Afghanistan’s cultural heritage and the need for international action at the 1997 World Heritage Committee meeting, yet the blowing up of the statues in early March 2001 was carried out under the eye of the international community. The Taliban only allowed a single Al-Jazeera’s journalist on the scene to broadcast live the final phase of the destruction, which brought the channel global exposure.[v] In addition, the numerous caves around the two statues, some of which once served as Buddhist shrines, remain at constant risk of looting to this day.[vi]

The weeks-long act of destruction caused considerable international outcry, and almost immediately a professional debate on the reconstruction of the statues was launched, which is still ongoing. The site, including the site of the Buddha statues, was included on UNESCO’s World Heritage List (and List of Sites in Danger) already after the atrocity in 2003, as “the most monumental expression of Western Buddhism”.

“The 333 holy cities” – Timbuktu mausoleums

The city of Timbuktu, in the north Mali desert, was occupied in spring 2012 by Islamist terrorist organisations linked to al-Qaeda’s North African branch (Ansar Dine and AQIM [al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb]). In the religious practice of the Sufi population, most of whom follow the more moderate strain of Islam, the veneration of the “saints” (the term “awliya’ allah” is actually best translated as “friends of God”, with a somewhat different meaning from the term “saint” used in Western Christianity) and thus the mausoleums, which serve as their burial places, has an important role to play.[vii] Shrines that were opposed to the extremist views of terrorist organisations were hammered in the summer of 2012. Evoking the vibrant scientific and spiritual atmosphere of Timbuktu in the 15th and 16th centuries, 14 mausoleums and 1 mosque in the city, a World Heritage site since 1988, have been destroyed or vandalised, using seriously barbaric methods. The attacks had an important symbolic value, and were aimed at destroying the religious customs built around these objects. The reconstruction of the holy places was completed within a few years, with considerable international support. Shortly before the attacks, UNESCO had included the complex of 16 mausoleums and 3 mosques on the List of World Heritage in Danger, and repeatedly called for the sites to be spared, but their destruction could not be prevented. However, the international community has shown ground-breaking results in terms of retaliation: in 2017, the International Criminal Court sentenced Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, a leading figure in the Ansar Dine organisation, to 9 years in prison for war crimes for the destruction of the religious heritage of the city, also known as the “Pearl of the Desert”. The Prosecutor General in the case stated: “not only a few walls and stones are at stake (…) To be sure, attacks on historic monuments and buildings dedicated to religion are de facto attacks on the very people that hold such tangible possessions near and dear to their cultural identity.“[viii]

Protection of Orthodox sites in Kosovo

The Dečan Monastery, a World Heritage site since 2004, was joined in 2006 by three other sites linked to the Serbian Orthodox Church, the monasteries of Peć, Gračanica and the Church of the Holy Virgin in Leviša, and is listed as a UNESCO “Medieval Monument in Kosovo” (and also on the List of Sites in Danger). Although the decision on the endangered status of the complex was taken in the post-war context, the unstable political situation and the unrest in 2004, during which several Orthodox shrines were attacked, led to the sites being placed under special international protection at the request of Serbia. Of these sites, the monastery of Dečan is still under the protection of the NATO Kosovo Force (KFOR).[ix]

We have seen from the above examples how built heritage, including objects of religious significance, can be sacrificed in a targeted manner at the altar of wider political-military objectives, whether merely rhetorically or by violent means. Wars can also cause collateral damage to buildings of particular value and with no military function. All of Syria’s six World Heritage Sites were severely damaged during the decade-long conflict, and the sacred sites were no exception. The medieval Umayyad mosque and its minaret in the World Heritage-protected Old City of Aleppo were damaged in 2013, while the Omar mosque in the ancient city of Bosra, one of the oldest remaining Islamic buildings, was also badly hit.[x] In the case of World Heritage sites, one means of preventive protection could be their inscription on the List of World Heritage Sites in Danger, which allows for a global allocation of professional and financial resources and international awareness-raising. And while there are negative experiences in practice, as we saw, in some cases inscription was either reactive or insufficient to avoid destruction, the World Heritage Convention and the mechanism it provides are an important element in the protection of our most outstanding cultural property in armed conflicts around the world.

[i] UNESCO World Heritage List

[ii] UNESCO Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest.

[iii] UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger.

[iv] Rod-ari, Melody: Bamiyan Buddhas. Khan Academy

[v] Bender, Larissa: Al-Jazeera – The Enigma from Qatar. Qantara.de, 6 November 2006.

[vi] O’Donnell, Lynne: The Taliban Take Aim at Buddhist Heritage. Foreign Policy, 7 June 2022

[vii] Ernst, Carl W.: Sufism, An Introduction to the Mystical Tradition of Islam. Shambhala Boston & London, 2011.

[ix] Petrick, Daniel: Is the Dečani Monastery Really Endangered? Kosovo 2.0., 28 July 2021.

[x] Izadi, Elahe: War has damaged all but one of Syria’s World Heritage Sites, satellite images show. The Washington Post, 24 September 2014