REVIEW – Scruton knew the past and present of East-Central Europe well. This is one of the reasons for it being worthwhile for the Hungarian reader to get to know Sir Roger’s work.

Roger Scruton did, indeed become fashionable shortly after his death. His popularity is growing noticeably, and not only in Hungary, where he has essentially been given the honorary role of philosopher of the national side. However, he is a particular representative of Anglo-Saxon conservatism. It is true that he learned a lot from Kant and Hegel, as well as from Burke and Oakeshott. He was also well versed in the past and present of Central and Eastern Europe. Therefore, since he familiarised himself with our culture, it is also worth it for a Hungarian reader to familiarise himself with Sir Roger’s work.

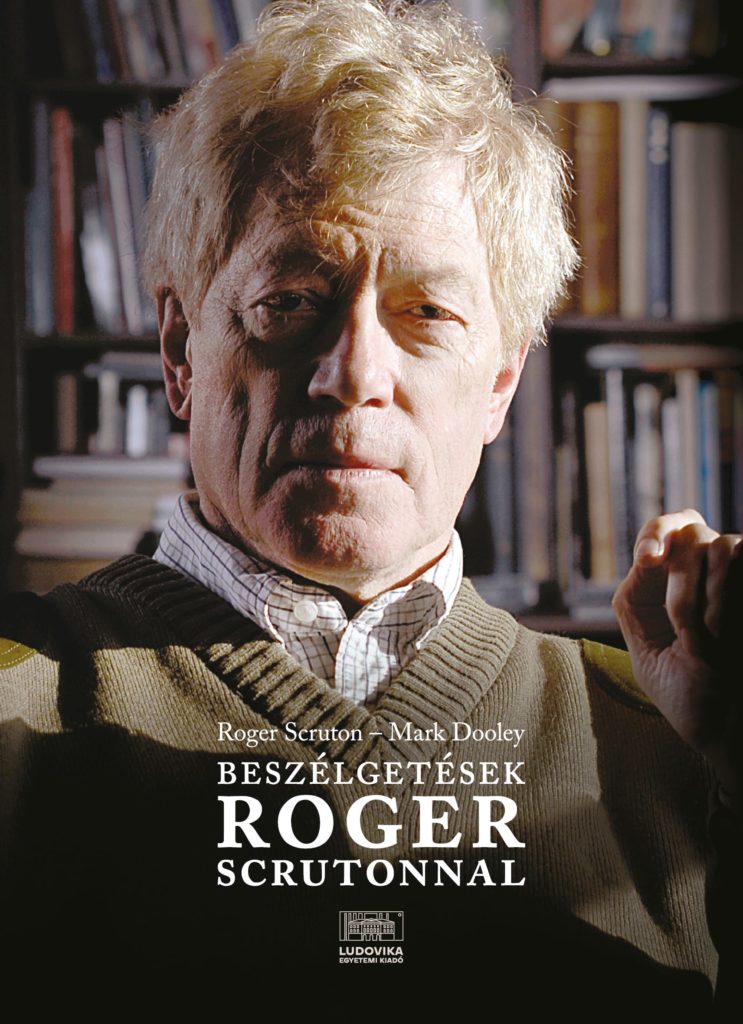

Ludovika Publishing, the reorganised and streamlined publisher of the Ludovika University of Public Service, just published its 2016 discussion book under the title Conversations with Roger Scruton. In this book, his interlocutor is Mark Dooley, a philosopher himself who knows Scruton’s work in depth and, already had a book published on it. In addition, the Hungarian edition also includes a foreword by Attila Károly Monár. The Conversations is actually a life story interview. It goes through the decisive turns in Scruton’s life and work and his intellectual development, and embeds it in a reconstruction of the intellectual movements of his era. In a separate chapter, he describes his Cambridge upbringing, his adventures in Eastern Europe, and his favourite philosophical themes, from the aesthetics of architecture and sexuality to music and the rediscovery of religion. See, for example, his criticism of the demolition of small towns: “I asked Scruton whether he thought that town planning had destroyed small towns like Marlow because of ideological considerations or ignorance. ‘Both. Ideology relegates knowledge. (…) I was only a child then, but I saw post-war Europe not only as a devastated continent with serious housing problems, but also as a guilt-ridden civilisation that had rigidly rejected its own past. After the two wars, people became uncertain about their own values, and buildings were the most important and unavoidable symbols of the values they inherited from the past. Our old buildings were witnesses to our wounded ideals, so the message they convey had to be erased at all costs.” (107).

A new, bibliophile edition of Scruton’s slim collection of essays, Confessions of a Heretic , was published at the same time as the Hungarian translation of the conversation book. The volume is accompanied by an introduction by the popular publicist and opinion leader Douglas Murray, which guarantees that Scruton’s work will reach a wide readership.

The genre of the confession is well known in the history of European thought; it is enough to refer to St. Augustine or Rousseau, both of whom published their own confessions. In these, the now canonical authors reviewed their lives themselves. Scruton does not undertake such a thing in this book. He picks some of his favourite themes. There are writings on the crisis of beauty, national feeling, building as an activity, music, conservation and the twilight of the West. Then he writes about what is a recurring theme in essay writing since Montaigne: what it means to die on time. This essay is made sadly evident by the author’s recent death.

For us, however, the most interesting of the writings in this volume is of course the one on governance. Scruton’s aim in writing this short and accessible piece is to disillusion conservatives of the delusion that government is necessarily something harmful. According to him, “government is the search for order, and can only be regarded as the search for power insofar as order presupposes power.” (37-38) While the conservative critique of government sees the protection of individual liberty as its task, the pro-government utilitarian position argues that government is really nothing more than “the other side of liberty, which enables liberty.” (38).

This starting point is closer to a Hegelian position than to a classical British conservative view, which regarded guaranteeing individual freedom as a basic condition. To this extent, the British Conservative was close to the classical Liberal. Scruton, as a conservative, does not give up any of the civil rights that the British constitutional tradition guarantees, including Habeas Corpus (1679) and the Bill of Rights (1689). Rather, it is about to trying to show what gives legitimacy to the government, even in a culture war context like ours.

Now, in addition to the function of government to seek order, Scruton discusses a further function. In his view, the human individual is a social construction. Although the latter term is familiar in mainstream, left-wing social theory, it is surprising that a conservative theorist uses it. Of course, he means something a little different from that of a social scientist. In fact, all he is saying is that the emergence of the personality or individual is an achievement of Western civilisation. To this extent, however, the individual needs government. But how is the individual born? Independence from others develops when an individual learns to take responsibility for their actions. In the Western paradigm, in our own tradition, we may become free individuals through assuming responsibility. Scruton’s example makes the dilemma tangible. He talks about how in America, the local crisis is quickly coming to an end because the neighbourhood is quickly coming together to deal with it, while Europeans sit helplessly by until the public servants arrive to help them out.

The government is therefore an enabler of civil society, and an outright supporter in the public space. The explanation for this is that they are created almost simultaneously, or even jointly. Government was originally established in small communities to solve coordination problems. As the community starts to grow, it controls more and more territory and has to reconcile a growing number of lifestyles and values. However, as the size increases, so do the coordination problems. After a while, governance becomes impossible: if the centre of power is too far away from the ordinary citizen, it will be less and less able to make the reluctant citizen obey the law.

This is when a Conservative must criticise the government. This is what is really needed when the governing powers govern for their own interests, not for the common good. However, the Conservatives expect a lot from the government anyway: for example, support for the deprived was part of their original programme. Even so, this obligation to support does not mean that Conservatives are moving towards the Rawlsian principle that the task of government is to distribute the goods produced by society. According to Conservatives, writes Scruton, the government must respect property rights over the produced goods.

The above principle does not imply that the Conservative position does not take the common good into account. On the contrary, Conservatives want a society led by the public spirit. Nevertheless, the spirit of commitment to the common good itself cannot be a gift from government: it is civil society that can “exploit” it. If the state intrudes into this territory, it can trigger the opposite effect to that intended. Public spirit is in fact the fruit of civil society, and in the long term only civil society, rather than the government can sustain it.In sum, the Conservative must be aware that their task is not merely to secure freedom from government, but to secure a better government. Here Scruton seems to depart consciously from Anglo-Saxon conservatism based on the traditional principle of the rule of law , and turn it towards the common good. In this sense, it is heretical from the point of view of British conservatism. He doesn’t put it that way, but I would be bold to say that what he is doing is establishing a kind of national conservative republicanism. Which is perhaps surprising for a UK citizen, but not surprising at all given the process leading up to Brexit and the emergence of a nationality-based conservatism. It is no coincidence that Scruton’s essay focuses on the word nation.

Source of the opening image: Flickr