In August 2025, the African Union (AU) formally endorsed “Correct the Map” campaign, an initiative urging reconsidering the way global geography is visualised.

At the heart of this campaign lies a deeply symbolic issue: the projection currently used in most world maps, the Mercator projection, was developed in 1569 by the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator. Originally designed to assist with navigation at sea, the Mercator projection does not reflect the true sizes of lands: it enlarges regions closer to the polesand reduces those near the equator. As a result, Africa appears to be similar in size to Canada or Europe, despite being significantly larger than the United States, China, and Europe combined.

Scholars have noted that such visual misrepresentations reflect the legacy of the colonial era, often reinforcing a Eurocentric perspective of spatial importance and power. In a 2025 interview with Reuters, African Union Commission Deputy Chair Selma Malika Haddadi said that such stereotypes influence media, education, and policy.

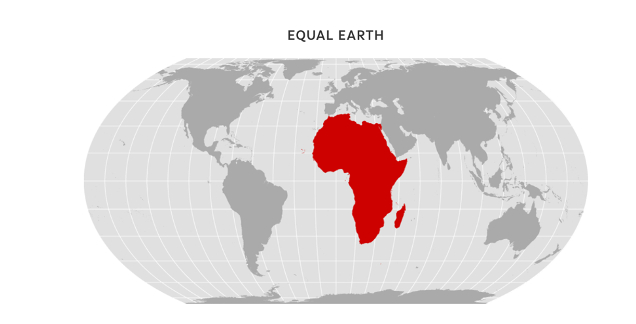

The campaign, “Correct My Map” is led by African civil society organisations “Africa No Filter” and “Speak Up Africa”, calling for the adoption of the Equal Earth projection instead of the widely used Mercator projection.

The Equal Earth projection was introduced by geographers Šavrič, Jenny, and Patterson in 2018 and offers an equal-area representation of the globe; that is, continents are drawn proportionally to their real surface areas, while keeping a visually familiar layout.

Following the official endorsement of the new map in August 2025, The African Union (AU) encouraged its 55 member states to adopt the Equal Earth projection. Since then, education ministries across the continent have begun reviewing geography curricula and maps.

According to Reuters, the ‘Correct the Map’ campaign has also reached out to international bodies such as the UN Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM) and UNESCO, urging them to align their educational and cartographic tools with equal-area standards. Public support is also being mobilised through open-access resources and an active petition.

Although this initiative is led by African civil society and endorsed by the African Union, its outcomes would reach far beyond the continent. For the world, including Europe, it would mean reconsidering how geography is taught and how the map is visualised, particularly in educational settings, political discourses, and public communication. Adopting the Equal Earth projection means that Europe would no longer appear larger than it truly is. While symbolic, such a change supports long-standing European commitments to fairness, evidence-based education, spatial literacy, and global awareness.

Why This Matters?

Maps are not only geographic tools. They shape how societies and individuals understand and perceive the world and their place within it, in terms of relevance, power, and potential. While no binding international standard has been adopted yet, more and more voices are calling for a fairer way to map the world. These efforts also align with the broader calls to decolonise knowledge systems, a growing area of interest among scholars and policymakers around the world.

Redrawing the map could be a first step toward reshaping how we see, understand, and relate to the world.

Map projections: Alyson Hurt / NPR

Image source: https://equal-earth.com/